'When you hear music, after it's over, it's gone, in the air. You can never capture it again.'I first encountered Eric Dolphy's name on the cover of his most famous solo album, Out to Lunch (Blue Note). I've seen it in a thousand jazz bargain bins, and it surfaces time and again in the classic all-time lists. It took me awhile to get my head around Dolphy's playing, whether it was the flute, the clarinet or the alto saxophone: his approach often sounded more like a cacophonous noise than an attempt to play, and the lack of coherency was something that completely turned me off. In some ways, I associated his playing with the spoofs and potshots often attributed to avant garde jazz: the image of the jazz musician as pretentious and aloof, making a ridiculous noise and calling it art.

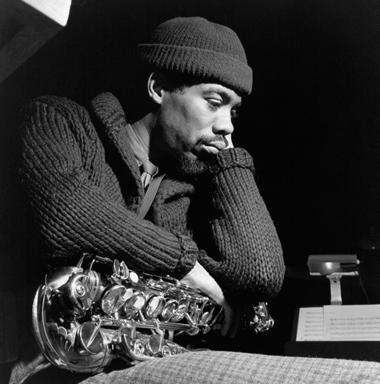

Eric Dolphy

So I put Out to Lunch to one side for awhile, and instead settled for more traditional jazz music. I have always been a great fan of Charles Mingus, not simply for his mastery of the double-bass but for his big, brash compositions - filled with an energy and a power that was invigorating for my walk home from work. I listened to Blues and Roots and Mingus Ah Um during this period, before extending myself toward some of the live recordings. Mingus at Antibes came at the top of this particular list, and I found myself playing it on my iPod every time I left the house. It was the perfect music for footsteps, and for a sense of gathering momentum.

Mingus is the master of powerful build-ups, and Mingus At Antibes includes some of his greatest works. But what makes them so precious is the fact that they are live life recordings: they are at times sloppy and disorganized, but the momentum carries each tune forward to its climax, and it's all completely captivating. There's a lust for life in this music that's difficult, if not impossible, to ignore. And in all honesty, I think that Charles Mingus was one of the key figures that drew me toward jazz music. The bass got you hooked, and the music carried you away. I can't even count the number of times I've listened to Mingus while walking down a busy city street, a beaming smile all over my face. It's joyous stuff.

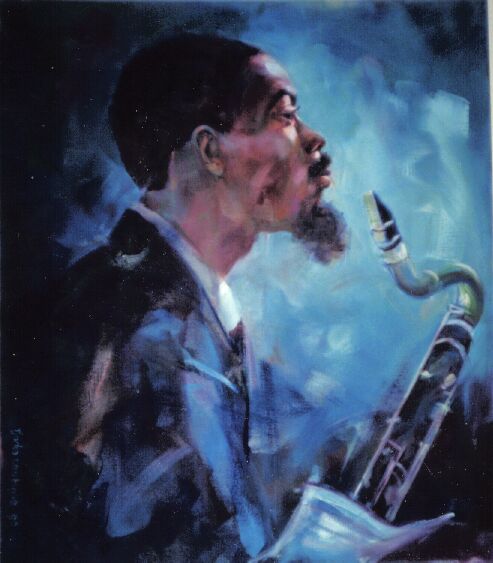

It was at this point that I discovered Eric Dolphy all over again, as an alto saxophonist in Mingus's band. There are seconds where the tumultuous storm of the music, or the swelling of the melody, falls into silence, and Dolphy takes over. The sound, or tone, of the instrument is so clear and unique, that you begin to hear it in other recordings as distinct and unique to Dolphy himself. Suddenly I could recognize him in a crowd: no one else plays like that.

But it wasn't just the sound of the instrument that stuck with me, but the notes he played. Eric Dolphy's approach would take something from the overall narrative of a given piece, and then blast off with something that was absolutely his own. This could mean a repetition of a main theme, or notes played in harmony with the rhythm, but at its apex it would dart and blast and resist all of these things at once. The music would suddenly take off in a saxophone solo that sounded simultaneously catchy and avant garde, although there was no longer a tune to be heard or grappled with. Eric Dolphy's solo would reduce each recording to a series of super-fast squeaks and squawks and crazy hell-bent yelps. But, by some miracle, you could tap your foot to it.

I started to hear some kind of logic in Dolphy's music from that point onwards. He fitted perfectly into the Mingus ensemble, and managed to bring something new to the table without detracting from the talent that was around him: they worked together seamlessly, in a way that added finesse and excitement and drama to the music. It gave each track the sense that it really was performed live and in the moment, and this has a captivating effect on the listener.

So I began to trace some of Eric Dolphy's solo work, from Out to Lunch to Outward Bound and Out There. A pattern begins to emerge, that self-consciously separates Dolphy from his time and place in the history of jazz: he continually positions himself outside of traditional, conventional musical standards and finds his niche in the exterior of avant garde music. This was the way many listeners identified with his work in the early 1960s, as his records were released, alongside other 'out there' musicians like alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman. But there is a little more tradition, and a little more coherence, than the album covers would have you believe.

One of the tracks that always gets me is a flute piece on Outward Bound called 'Glad to be Unhappy'. It's a simple melody with a slow bass accompaniment, and a quiet piano playing softly in the background. The tune is driven by Dolphy's flute-playing, and superbly evokes the title with a sense of wallowing and melancholy. There is a lyrical improvisation halfway through the track, which wonderfully captures the paradoxical sense of happiness that a depressed state can bring, before recounting the original melody and tone at the end. It's perfect night-listening, and I never tire of it.

Rather than adopting a strictly 'out to lunch' style, leaping out into the dark of chaotic, frenetic free jazz 'noise', Eric Dolphy achieves a welcome balance between rhythm, melody, and the occasional offshoot into bewildering mess. But, when I call it a mess, I don't mean it in a dismissive way (believe it or not). Dolphy's gift is in finding harmony between the harmonious and the disharmonious, and running with it, with compositions that feel like they have a logic and a rationale all of their own. And the result gives off the most fantastic feeling. Each recording is blistering with invention and virtuosity, while retaining the sense of atmosphere and resonance that all those great 1950s records had to offer.

While on a European tour in 1964, Dolphy suddenly collapsed, and later died in a diabetic coma. A tragic event, occurring just as recognition and success was beginning to dawn. He had featured on a number of records by Charles Mingus, by this time a close personal friend, and had worked on Andrew Hill's Point of Departure. He was also familiar with musicians like Bobby Hutcherson and Herbie Hancock, who were not only influenced by Dolphy's work but later became great in their own right.

For those interested in exploring some of Eric Dolphy's music, AllAboutJazz offers its own biography of the virtuoso, alongside reviews and retrospectives of his work. You can view their profile of Dolphy by clicking here.