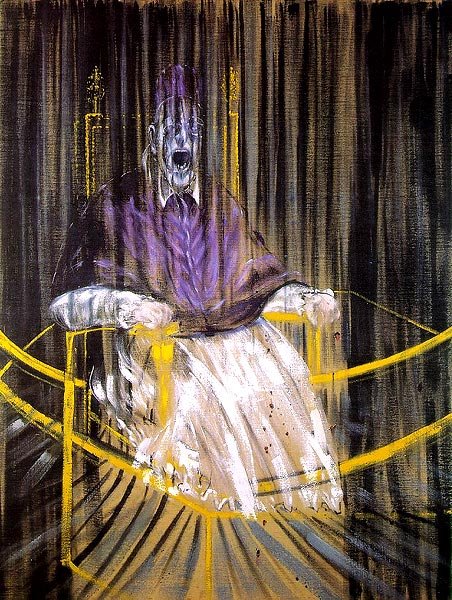

Contemporary writer Ballard on the dark visions of the late Irish painter

Excerpted from J. G. Ballard,

Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton:

'In 1955 there was a modest retrospective of Francis Bacon's paintings at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, followed in 1962 by a far larger retrospective at the Tate Gallery, which was a revelation to me. I still think of Bacon as the greatest painter of the post-war world.' [...]

'Bacon's paintings were screams from the abattoir, cries from the execution pits of World War II. His deranged executives and his princes of death in their pontiffs' robes lacked all pity and remorse. His popes screamed because they knew there was no God. Bacon went even further than the surrealists, assuming our complicity in the mid-century's horrors. It was we who sat in those claustrophobic rooms, like TV hospitality suites in need of a coat of paint, under a naked light bulb that might signal the arrival of the dead, the only witnesses at our last interview.

'Yet Bacon kept hope alive at a dark time, and looking at his paintings gave me a surge of confidence. I knew there was a link of some kind with the surrealists, with the dead doctors lying in their wooden chests in the dissecting room, with the film noir and with the peacock and the loaf of bread in Crivelli's 'Annunciation'. There were links to Hemingway and Camus and Nathanael West. A jigsaw inside my head was trying to assemble itself, but the picture when it finally emerged would appear in an unexpected place.'