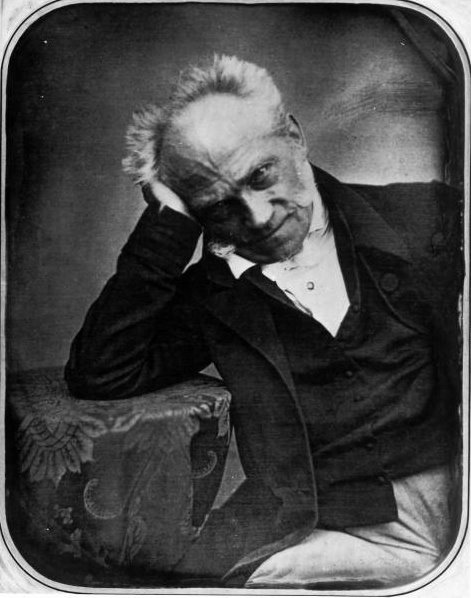

An excerpt from R. J. Hollingdale's excellent introduction to Essays and Aphorisms

From the age of 45 until his death 27 years later Schopenhauer lived in Frankfurt-am-Main. He lived alone, in ‘rooms’, and every day for 27 years he followed an identical routine. He rose every morning a seven and had a bath but no breakfast: he drank a cup of strong coffee before sitting down at his desk and writing until noon. At noon he ceased work for the day and spent half-an-hour practicing the flute, on which he became quite a skilled performer. Then he went out for lunch at the Englischer Hof. After lunch he returned home and read until four, when he left for his daily walk: he walked for two hours no matter what the weather. At six o’clock he visited the reading room of the library and read The Times. In the evening he attended the theatre or a concert, after which he had dinner at a hotel or restaurant. He got back home between nine and ten and went early to bed. He was willing to deviate from this routine in order to receive visitors.

R. J. Hollingdale, Introduction toArthur Schopenhauer, Essays and Aphorisms

Translator and scholar of German philosophy R. J. Hollingdale speculates on what Schopenhauer’s daily routine could tell us about both his character and his philosophical work:

[…] If we try for a non-emotive description we might call it the inability to abandon or modify an attitude of mind once adopted. Consider the daily two-hour walk. Among Schopenhauer’s disciples of the late nineteenth century this walk was a celebrated fact of his biography, and it was so because of its regularity. There was speculation as to why he insisted on going out and staying out for two hours no matter what the weather. It suggests health fanaticism, but there is no other evidence that Schopenhauer was a health fanatic or a crank. In my view the reason was simple obstinacy: he would go out and nothing would stop him. It is a minor manifestation of that rooted immovability of mind. […]

My purpose in flogging this point it to try to make it seem at any rate possible that, if a pessimistic attitude towards life had grown up in Schopenhauer’s mind as a result of his early experience of it, that attitude would persist unchanged throughout his adult years and down to his death; so that the cause of his pessimistic disposition could plausibly be sought in youthful experiences which, while in themselves not at all uncommon, might make on him an uncommonly lasting impression. What would then be singular about Schopenhauer would not be his pessimism itself but only the fact that it endured long enough for him to bring to its exposition and analysis the power of a very gifted adult intelligence. For that disillusionment with life which Schopenhauer expounds and tried to account for in almost all his writings was the consequence not of any unique for very uncommon occurrence but of experiences which tens of thousands and perhaps millions of other young men have undergone in our epoch, experiences which have brought the taste of ashes to their mouth and whose effects they have overcome or even forgotten simply because they lacked Schopenhauer’s immovability of mind.

R. J. Hollingdale, Introduction toArthur Schopenhauer, Essays and Aphorisms