Part of a series of short essays published in The Guardian

Conscience is a call. It is something that calls one away from one's inauthentic immersion in the homely familiarity of everyday life. It is, Heidegger writes, that uncanny experience of something like an external voice in one's head that pulls one out of the hubbub and chatter of life in the world and arrests our ceaseless busyness.

This sounds very close to the Christian experience of conscience that one finds in Augustine or Luther. In Book 8 of the Confessions, Augustine describes the entire drama of conversion in terms of hearing an external voice, "as of a child", that leads him to take up the Bible and eventually turn away from paganism and towards Christ. Luther describes conscience as the work of God in the mind of man.

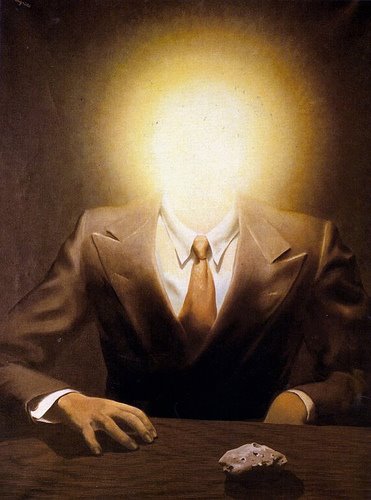

For Heidegger, by contrast, conscience is not God talking to me, but me talking to myself. The uncanny call of conscience – the pang and pain of its sudden appearance – feels like an alien voice, but is, Heidegger insists, Dasein calling to itself. I am called back from inauthentic life in the world, complete with what Sartre would call its "counterfeit immortality", towards myself. Furthermore, that self is, as we saw in blog 6, defined in terms of being-towards-death. So, conscience is the experience of the human being calling itself back to its mortality, a little like Hamlet in the grave with Yorick's skull.

What gets said in the call of conscience? Heidegger is crystal clear: like Cordelia in King Lear, nothing is said. The call of conscience is silent. It contains no instructions or advice. In order to understand this, it is important to grasp that, for Heidegger, inauthentic life is characterised by chatter – for example, the ever-ambiguous hubbub of the blogosphere. Conscience calls Dasein back from this chatter silently. It has the character of what Heidegger calls "reticence" (Verschwiegenheit), which is the privileged mode of language in Heidegger. So, the call of conscience is a silent call that silences the chatter of the world and brings me back to myself.

Read part one: 'Being and Time, part 1: Why Heidegger matters'.

Read part two: 'Being and Time, part 2: On 'mineness''.

Read part three: 'Being and Time, part 3: Being-in-the-world'.

Read part four: 'Being and Time, part 4: 'Thrown into this world'.

Read part five: 'Being and Time, part 5: 'Anxiety'.

Read part six: 'Being and Time, part 6: 'Death'.