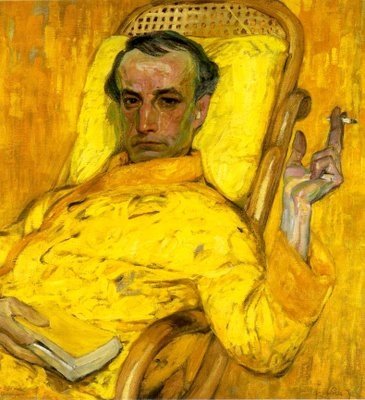

Why I'm beginning to feel like Joris-Karl Huysmans

I'm reminded of Des Esseintes, the typically melodramatic aesthete of A Rebours, whose misanthropy and impatience lead him no alternative but the solitary life. His disdain for the madding crowd and reluctance to be a part of society is intended to be witty and ironic; but like all great comedy, it is founded upon an underlying tension. I am not a hater of mankind, by any means, and there is nothing greater for me than time spent in good company, but I can see the point Des Esseintes is making. I wonder what he might have thought of my old living quarters, and in contrast, what he would make our 'snugly heated ark' here in Penarth:

Little by little, he dropped these people and sought the society of men of letters, imagining that theirs must surely be kindred spirits with which his own mind would feel more at ease. A fresh disappointment lay in store for him: he was revolted by their mean, spiteful judgements, their conversation that was as commonplace as a church-door, and the nauseating discussions in which they gauged the merit of a book by the number of editions it went through and the profits from its sale. At the same time, he discovered the free-thinkers, those bourgeois doctrinaires who clamoured for absolute liberty in order to stifle the opinions of other people, to be nothing but a set of greedy, shameless hypocrites whose intelligence he rated lower than the village cobbler's.

His contempt for humanity grew fiercer, and at last he came to realize that the world is made up mostly of fools and scoundrels. It became perfectly clear to him that he could entertain no hope of finding in someone else the same aspirations and antipathies; no hope of linking up with a mind which, like his own, took pleasure in a life of studious decrepitude; no hope of associating an intelligence as sharp and wayward as his own with that of any author of scholar.

He felt irritable and ill at ease; exasperated by the triviality of the ideas normally bandied about, he came to resemble those mentioned by Nicole who are sensitive to anything and everything. He was constantly coming across some new source of offence, wincing at the patriotic and political twaddle served up in the papers every morning, and exaggerating the importance of the triumphs which an omnipotent public reserves at all times and in all circumstances for works written without thought or style.

Already he had begun dreaming of a refined Thebaid, a desert hermitage equipped with all modern conveniences, a snugly heated ark on dry land in which he might take refuge from the incessant deluge of human stupidity.

Joris-Karl Huysmans, Against Nature (A Rebours)