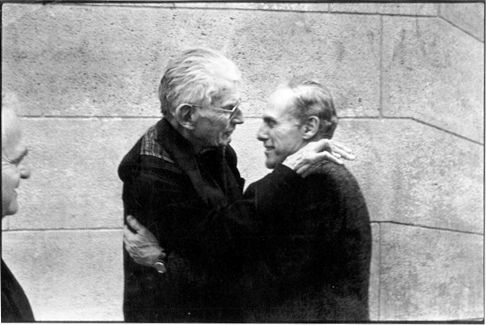

American publisher Barney Rosset reflects on his long friendship with the European writer

American publisher Barney Rosset tells Belinda McKeon of the day Samuel Beckett was lost in New York, and recounts anecdotes of their long-standing friendship:

Beckett and Rosset saw each other several times a year, but mostly in Paris, and Rosset always did the travelling. Except, that is, for one occasion - Beckett's sole visit to the US, in the summer of 1964. The trip was officially a working holiday; Rosset had commissioned Beckett to write a film script, and the result, a silent piece called Film, starring Buster Keaton and directed by Alan Schneider (an experienced director of Beckett's works onstage, but here on his first film project), was shot in lower Manhattan.

The omens for a pleasant stay were not good - it was high summer, the heat was sweltering and the shoot went badly in many respects, with one long, central shot having to be scrapped altogether. But Beckett seems to have enjoyed himself immensely. He became fascinated with the technical challenges of making the film, which concerned itself with the tension inherent in the act of perception - between seeing and being seen - and he was involved with every step of the process, from scouting for locations to editing a first rough cut. Though his personal encounter with Keaton was painfully awkward - Keaton sunk in silence, Beckett trying to spark conversation - he enjoyed watching him act. And there were other pleasures, from bar-hopping with Rosset, Schneider and others to meeting Edward Albee; from theatre-going to an afternoon at a baseball game, at which Beckett became an unlikely, but utterly absorbed, fan of the Mets.

Above: Buster Keaton on the set of Film (1965); Samuel Beckett standing in background. Click photograph to enlarge.

It's of Beckett's somewhat farcical last day in New York, however, that Rosset has the fondest memories; having planned to drive their guest to the airport, he and his wife overslept on that morning and woke to find Beckett asleep against their bedroom door; his bags packed, his overcoat on, he had been too polite to wake them. His plane was gone, so they spent the day at the World's Fair in Queens - and promptly lost Beckett, only to find him on a bench in the midst of the crowds, once more asleep and once more in the heavy overcoat.

The anecdotes give glimpses of the Beckett that Rosset knew, a different Beckett, certainly, than the evidence of the plays and prose might lead readers to imagine. This was a man as warm as he was wry; serious and intensely private, yes, but also comical, curious, deeply compassionate. Above all, he was generous. Rosset remembers a payment for thousands of dollars arriving for Beckett at the offices of Grove; Beckett insisted immediately that it be sent to the widow of Sean O'Casey in Dublin, of whom he was extremely fond.

When Rosset was sacked by the people to whom he decided to sell Grove, the day before Beckett's 80th birthday, Beckett made him a present of an unpublished play - Eleuthéria, his first complete dramatic work which he had written in French in 1947 - to get him started in his new venture. When the task of translating Eleuthéria into English frustrated him, he completed instead another work, Stirrings Still, to be published by Rosset's new house, Blue Moon Books. "Oh all to end," it concluded, and it was to be an end indeed. Although Beckett wrote a last poem, What is the Word, in his hospital bed, Stirrings Still was his final book.

Rosset was with him close to the end, in the nursing home where he spent his final months. Very soon before his death, Rosset brought him a tape of the famous production of Godot at the high-security prison in San Quentin, California. He didn't know at the time, he says, just how advanced Beckett's emphysema was at the time, just how close to death he was.

Among all the books and papers that Rosset has taken out for our conversation is a photograph he took of Beckett that day, in his bedroom at that nursing home, staring at a tiny television screen. On the table in front of him is a bottle of Tullamore Dew; on his face is a look of absolute concentration. He did not watch his last Godot in silence; Rosset remembers how, as the actors moved on screen, he reached out, silently signalled to them, directed them, as they grappled with the characters he had made. A creator, and a communicator, to the very last.

- A Piece of Monologue: Samuel Beckett and the Grove Press

- A Piece of Monologue: Waiting for Beckett Documentary

- The Paris Review: Barney Rosset