Review of Ballard's autobiography

Since the news of the death of British writer J. G. Ballard last month, I've been revisiting some of his work. I felt a great affinity with many of his short stories while an undergraduate at university, and developed a bond with his novels while working full-time at a city multiplex cinema.'But perhaps there was an answer, using a kind of extreme logic. My direction as a writer changed after Mary's death, and many readers thought that I became far darker. But I like to think I was much more radical, in a desperate attempt to prove that black was white, that two and two made five in the moral arithmetic of the 1960s. I was trying to construct an imaginative logic that made sense of Mary's death and would prove that the assassination of President Kennedy and he countless deaths of the Second World War had been worthwhile or even meaningful in some as yet undiscovered way. Then, perhaps, the ghosts inside my head, the old beggar under his quilt of snow, the strangled Chinese at the railway station, Kennedy and my young wife, could be laid to rest.'

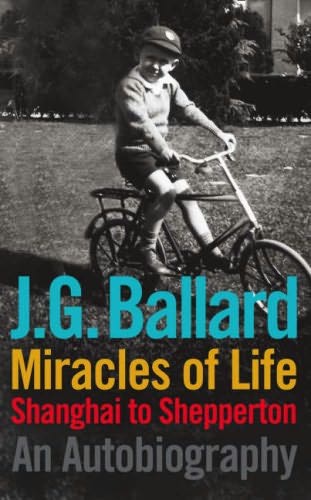

J. G. Ballard, 'Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton'

Ballard's themes feel more like obsessions, constantly recurring through the body of his work, like the neurotic symptoms of a psychoanalytic patient. His writing stemmed from an interest in contemporary life as he saw it, and within the strange contradictions of the middle-class nuclear family, or the dark and unspoken underside of Western society. Ballard's work explores the surreal relationship of the transgressive or the extreme with the realities of everyday life. He was among the first to explore the implications of aspirational consumerism on the human subject, and the construction of Western consciousness through the media cult of celebrity.

All of his narratives appear to share a common vocabulary of images, of abandoned car parks and empty swimming pools, icons of modernity that are somehow deconstructed and undermined. These images, with their persistent recurrence in so many of Ballard's novels and short stories, strike a chord with the reader as uncanny signifiers of a world that no longer exists. The major traumatic events of twentieth-century history have, in a sense, devalued rationalist notions of logic and structure, and so have devalued the security of truth and of meaning. Ballard's canvas offers a landscape of a derelict modernity, formed in the context of the Second World War, the Kennedy assassination, and the Holocaust.

Ballard has cited the surrealist painters as a key influence on his work, and it is often clear to see. The surrealist manifesto questions and undermines the natural order of things: images and signifiers are juxtaposed in ways that defy rationalization, often leading to the kind of confusion or incoherence that denies observers comfort or security. Such works purposefully lack the promise or closure of any stable, unitary meaning, and for many this can be a deeply troubling conclusion.

It's easy to see Ballard's work refracted through key events of twentieth-century history, where his middle-class childhood afforded him an observer's perspective on the poverty and violence that surrounded him. In many ways his eyewitness testimony is a surrealist guidebook of twentieth-century history: a troubled and terrible list of fractured bodies, abandoned buildings and crumbling civilizations. There is the potent and incompatible blend of the large suburban home and the dead beggar at the foot of the driveway, or street-level businesses existing in and around bombed-out buildings. Surrealist combinations that defy all sense or reason, but also in some way define what it means to exist in the twentieth-century.

J. G. Ballard's Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton is a book written in hindsight. Already aware that he is suffering from a terminal illness, Ballard intended to shed some light on a life that is rich in anecdotal details. Raised in Shanghai, Ballard was interned in a camp by Japanese troops during the wartime occupation of China. After the war he migrated to England, where he became a medical student examining cadavers at Cambridge University. He began to form profound opinions on the life and complexity of the human body, but decided that while the experience provided fertile ground for his imagination, he was not motivated to become a doctor. The course in medicine had in fact been an attempt to move into a career in psychiatry, trying to understand the mind in order to understand himself.

Miracles of Life is both candid and compelling, offering new insights into the artistic motivations of one of Britain's greatest authors. There is a detailed exploration of his childhood experiences in Shanghai, and a number of attempts to sketch a reason or logic for the shape that his fiction was to take. The autobiography also accounts for the tragic loss of his wife, and the immense difficulty of reconciling everyday life with such random, seemingly meaningless events.

Ballard's novels appear to chart the 'inner-space' of protagonists who are undergoing profound mental trauma, defined in the context of post-war Western society: a culture defined by the mass media, celebrity, consumerism and advanced technology.

J. G. Ballard's final book does not answer every question, or explain every obsession, but is a new work in its own right. It presents us with the last of Ballard's protagonists, consummately played by the writer himself: a man of comfortable, middle-class upbringing, surrounded by an affectionate family in a quiet, idyllic neighbourhood. And yet, this man, who embodied the quintessential aspirations of Western society, is ultimately defined by the incoherent trauma of the century that created him. A fascinating memoir of a fascinating life.