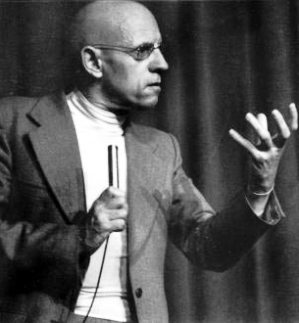

French cultural theorist and historian on the influence of Samuel Beckett's work

Excerpted from James Miller,

The Passion of Michel Foucault:

Foucault's own youthful epiphany was not nearly so sudden. It all began, as he later recalled, in a darkened theater one night in the winter of 1953.

The curtain went up, and revealed a barren set. Just the skeleton of a tree. On stage appeared two tramps. "Nothing to be done," says one. "I'm beginning to come round to that opinion," says the other.

Of no discernible age or calling, the tramps chatter idly.

"What about hanging ourselves," says one.

"Hmmm. It'd give us an erection," says the other.

"An erection! ... Let's hang ourselves immediately.'

But this exchange, like every other, comes to nothing.

Off stage, a whip cracks. A man appears, leading a slave tethered to a rope tied around his neck. "I present myself," the master says with pompous grandiloquence: "Pozzo"

A play-within-theplay unfolds. The slave will perform. Pozzo jerks the rope: "Think, pig!" The otherwise mute man abruptly lurhces into a shouted soliloquy: "Given the existence as uttered forth in the public works of Puncher and Wattmann of a personal God quaquaquaqua with white beard quaquaquaqua outside time without extension who from the heights of divine apathia divine athambia divine aphasia loves us dearly with some exceptions for reasons unknown but time will tell..."

This explosion of words is doubtless the most exciting single moment in a nearly three-hour performance. For the rest, it is a matter of endless waiting - waiting for someone called Godot.

Samuel Beckett's play was the intellectual event of that season in Paris. It rocked the intelligentsia, such as Sartre's lecture on existentialism had eight years before. Night after night, audiences sat solemnly, as if watching a dramatization of Heidegger's philosophy - which is precisely what the young novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet declared the play to be. A farce with the air of tragedy, its vagrant heroes had nothing to do and little to say, their hyponotically boring patter broken only by the slave's mad parody of scholasticism. Offered as a kind of philosophical parable, the play seduced Parisian audiences with its irresistible hints of a deep and important mystery just waiting to be unravelled.

It is obvious, Robbe-Grillet declared in his influential review, that Godot is God: "After all, why not? Godot - why not, just as well? - is the earthly ideal of a better social order. Do we not aspire to a better life, better food, better clothes, as well as the possibility of no longer being beaten? And this Pozzo, who is precisely not Godot - is he not the man who keeps thought enslaved? Or else Godot is death: tomorrow we will hang ourselves, if it does not come all by itself. Godot is silence; we must speak while waiting for it: in order to have the right, ultimately, to keep still. Godot is that inaccessible self Beckett pursues through his entire oeuvre, with this constant hope, 'This time, perhaps, it will be me at last.'"

Shortly before his death, Foucault summed up his intellectual odyssey in these years. "I belong to that generation who, as students, had before their eyes, and were limited by, a horizon consisting of Marxism, phenomenology, and existentialism," he said. "For me the break was first Beckett's Waiting for Godot, a breathtaking performance."

That this drama of futility, folly, and aborted metaphysics should have suggested the best way yet to escape from Sartre's "terrorism" is not accidental. The world of Godot is a world where the very ideas of freedom and responsiobility have been dramatically emptied of any lingering moral significance. "Moral values are not accessible," Beckett would later declare. "It is not even possible to talk about truth, that's part of the anguish. Paradoxically, through form, by giving form to what is formless, the artist can find a possible way out."

In the winter of 1953, Foucault had yet to invent his own "possible way out." But that would come soon enough. For this time, perhaps, it was himself, at last, that he was finding.