Colin Dickey reviews a 'mature' posthumous work

|

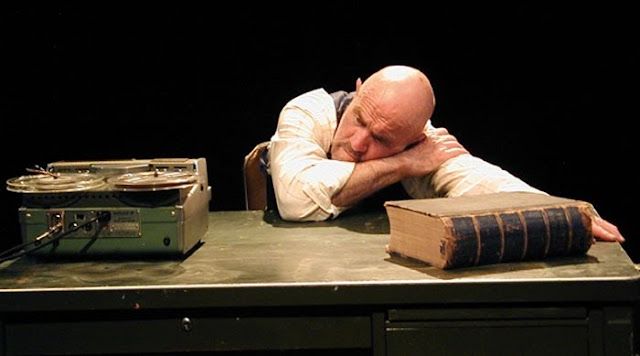

| W. G. Sebald |

Though his life was tragically cut short at the height of his creative powers, W. G. Sebald has been steadily churning out work since his death. Sebald’s posthumous publications have, by and large, followed a now-standard pattern: first were the works already or nearly finished and ready for print (On the Natural History of Destruction, After Nature), then the uncollected essays which offered polished, self-contained pieces (Campo Santo), then the book of interviews, along with the books of minor poetry for which he was not primarily known (Unrecounted, Across the Land and the Water). This last, released in 2012, would seem to have been the beginning of the end of this vast reserve—Sebald’s minor poetry is interesting at times, but far below the quality of his prose works or his masterful poetic work After Nature. Reaching the end of a finite supply, it would seem that the only place left to go would be to journals, fragments of essays, or other ephemera.

Instead, 2014 sees the release in the United States of A Place in the Country: a full prose work published originally in German in 1998, between The Rings of Saturn and Austerlitz—in other words, at the height of Sebald’s literary career. The book is a series of essays on five writers (Johann Peter Hebel, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Eduard Mörike, Gottfried Keller, and Robert Walser) and one painter (Jan Peter Tripp), the product of what he describes, in the foreword, as an “unwavering affection for Hebel, Keller and Walser,” which in turn “gave me the idea that I should pay my respects to them before, perhaps, it may be too late.” A haunting phrase, given his death only three years after the book’s publication—but one that also accurately sums up the admiration and homage that runs through the book, a writer engaging with his forebears and tracing his own literary genealogy through the past two centuries.

Not just scraps or isolated essays, it is a mature, fully realized book. While a few of the pieces were originally written separately, they’ve all been thoroughly interwoven into a holistic and coherent book, one much closer in form and ambition to The Emigrants than it is to Campo Santo. And yet it’s been withheld from an English translation for fifteen years, even as the reading public has been gobbling up lesser work. [Read More]

Find on Amazon: US | UK

Also at A Piece of Monologue:

_-_ritr._A_Ferrazzi,_Recanati,_casa_Leopardi.jpg)

Well, I'm back in the United Kingdom after a month in California. I arrived at Heathrow Airport's Terminal 5 early yesterday morning, and jetlag has prevented me from snatching more than five or six hours of sleep. As a result, I'm spending my early morning hours drinking plenty of water and catching up on a spot of reading.

Well, I'm back in the United Kingdom after a month in California. I arrived at Heathrow Airport's Terminal 5 early yesterday morning, and jetlag has prevented me from snatching more than five or six hours of sleep. As a result, I'm spending my early morning hours drinking plenty of water and catching up on a spot of reading.