Your guide to this week's best cultural links

|

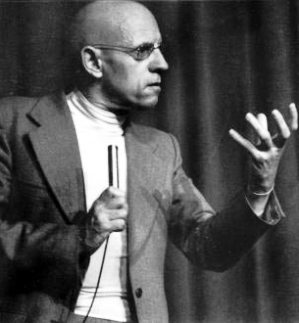

| Woody Allen |

Literature:

Samuel Beckett: Volume 2 of

The Letters of Samuel Beckett, covering the years 1941-1956, to be released August 2011

Samuel Beckett: Grove Atlantic release

The Selected Works of Samuel Beckett

Samuel Beckett: This weeks Ends and Odds from the

Debts and Legacies website

Samuel Beckett: BookGeeks reviews the new Faber edition of

Company, and other short prose works.

Samuel Beckett: Beckett included in a recent

Irish Times article about resistance heroes of the Second World War

Margaret Atwood: The Handmaid's Tale celebrates its 25th Anniversary this year

Joyce Carol Oates: HarperCollins release

Sourland, a new collection of short stories

J. M. Coetzee: Patrick McGrath reviews

The Master of Petersburg

Michel Houellebecq: 2010 Interview in

The Paris Review

25 words of fewer: 'Hint fiction'

Ian McEwan: Could British novelist's son hold cure for the common cold?

J. G. Ballard: Norton releases

The Complete Short Stories in Paperback

Paul Auster: Biblioklept compiles six online interviews with the American author

Paul Auster: Interview with Paul Auster about his new novel,

Sunset Park

Paul Auster's favourite books

Paul Auster: Borders interviews Auster about

Sunset Park

Paul Auster on Book Reviews: Interview in the

Wall Street Journal

Don DeLillo: A review of what is perhaps DeLillo's signature novel,

White Noise

English Literature: A very short introduction: Jonathan Bate's guide reviewed in

The Independent

AHRC: Funding opportunity for 'a new generation of thinkers'

wwword: A new website for lovers of language and literature

Philosophy & Critical Theory:

Assuming Gender: Annual Lecture at Cardiff University, 1 December, free to attend

Simon Critchley: Interview with

Frieze

Shakespeare and Derrida: Call for Papers

Roland Barthes on Alain Robbe-Grillet

Theatre:

Samuel Beckett: New production of

Happy Days produced by the Corn Exchange in Dublin

Samuel Beckett: Mary Bryden unravels the cultural and historical significance of Beckett's Godot

Samuel Beckett: Queen Elizabeth is reportedly a fan of

Waiting for Godot

Samuel Beckett: Michael Lawrence writes and stars in

Krapp, 39, a personal adaptation of Beckett's

Krapp's Last Tape

William Shakespeare: Fabler Shakespeare Readers in Cardiff

Music

Bob Dylan After the Fall: NYRB reviews writings on Dylan by Sean Wilentz and Greil Marcus

Franz Kafka: Review of György Kurtág's

Fragments

Film

Woody Allen: Illustrated online biography of the early Woody Allen, 1952-1971

Thank you to all link contributors, who can be found on the A Piece of Monologue Twitter page.